Among the Royal Ontario Museum’s collections in Toronto, Canada’s largest city, Korean paintings catch the eye. In an era before photography or video recording, paintings served as both art and documentation, and also as a way to express hopes for a better life.

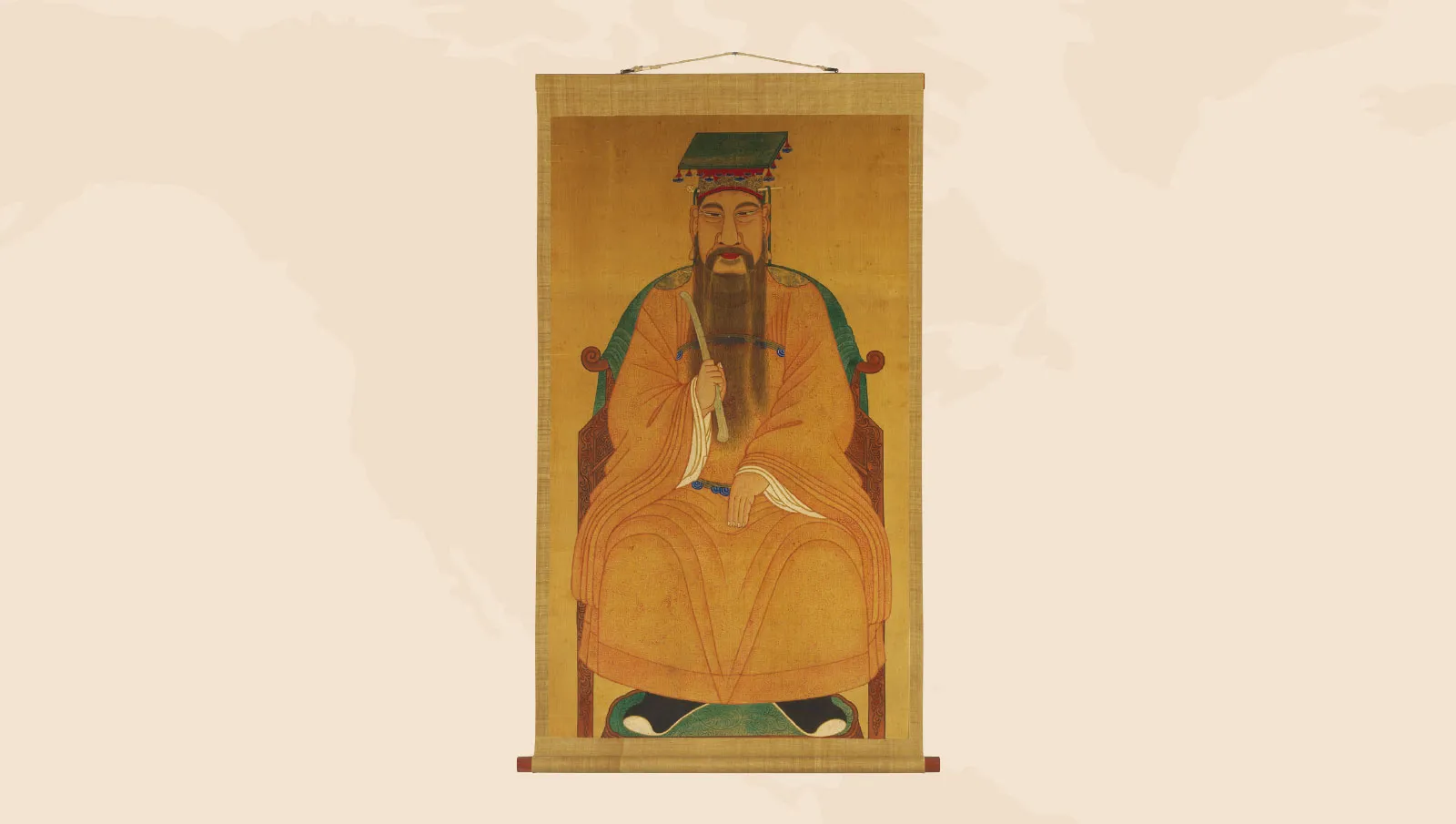

Consider the museum’s late 19th-century minhwa (folk painting) of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910), the “Great Jade Emperor.” A figure sits on a chair wearing reddish-yellow robes adorned with gold decoration. Gold embellishment also adorns the hat, waist belt and sash, while thick eyebrows, a long flowing beard, and even the skin texture around the eyes are rendered with delicate precision. The solemn, humorless expression and the hierarchy evident in the costume reveal this figure’s high authority.

As the title indicates, this painting depicts the “Great Jade Emperor,” a deity highly revered in popular belief at the time. The Great Jade Emperor, supreme ruler of heaven, originated as a Taoist deity but entered Korean folk culture through shamanistic beliefs. Regarded as the being governing human longevity, health, and fortune both good and ill, people painted and worshipped his image to ward off calamity and pray for blessings.

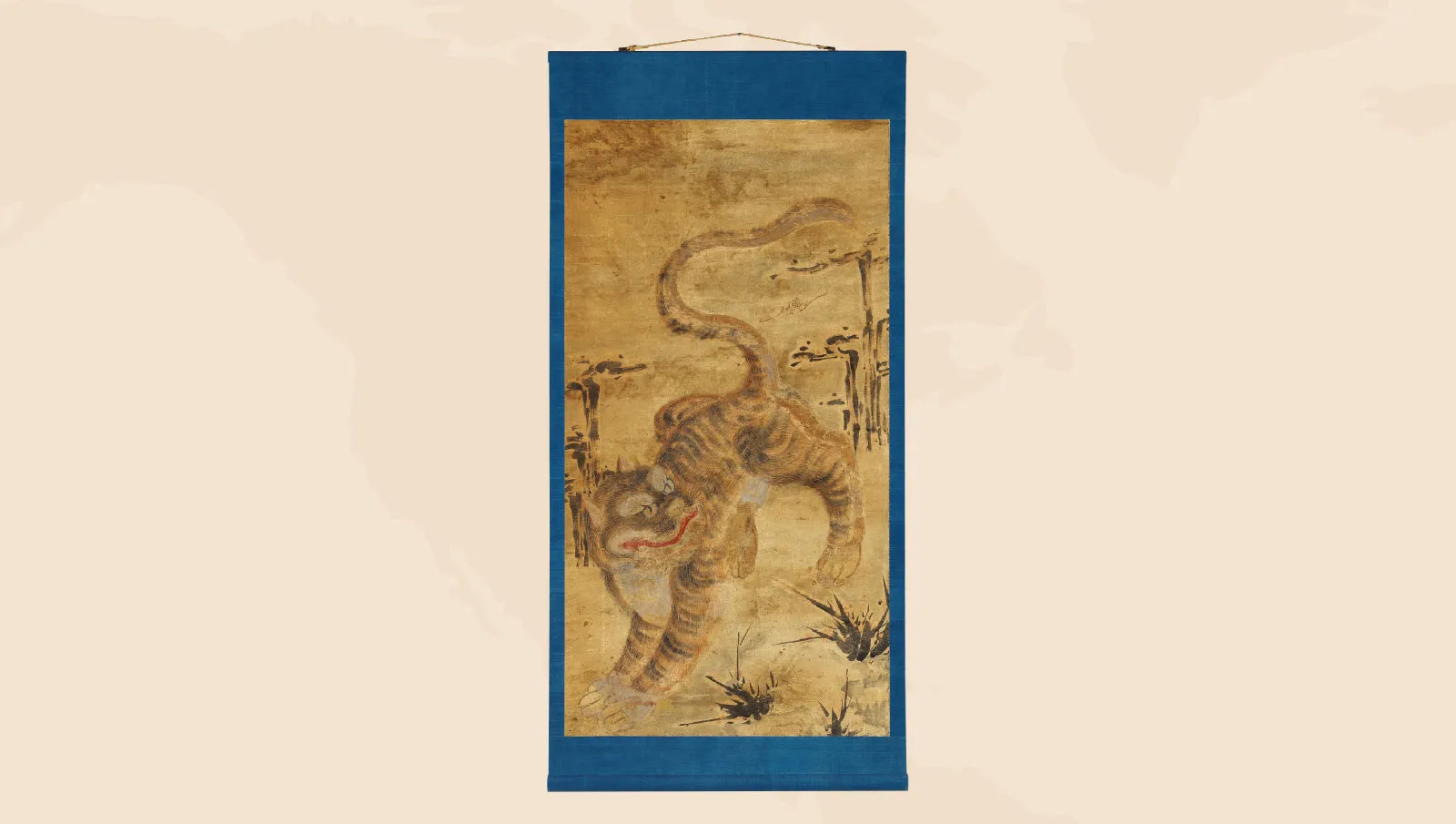

The museum’s companion pieces—”Tiger,” “Dragon God” and “Byeolsang God”—are minhwa created in the same context. “Tiger” captures a tiger, a symbol of power that wards off misfortune, gazing at a bat. “Dragon God” depicts a man with a dragon—a symbol of protection and abundance—in the background, illustrating the dragon’s favor upon him. “Byeolsang God” portrays a deity who protects the nation and household from harm, appropriately rendered in military dress to reflect this role.

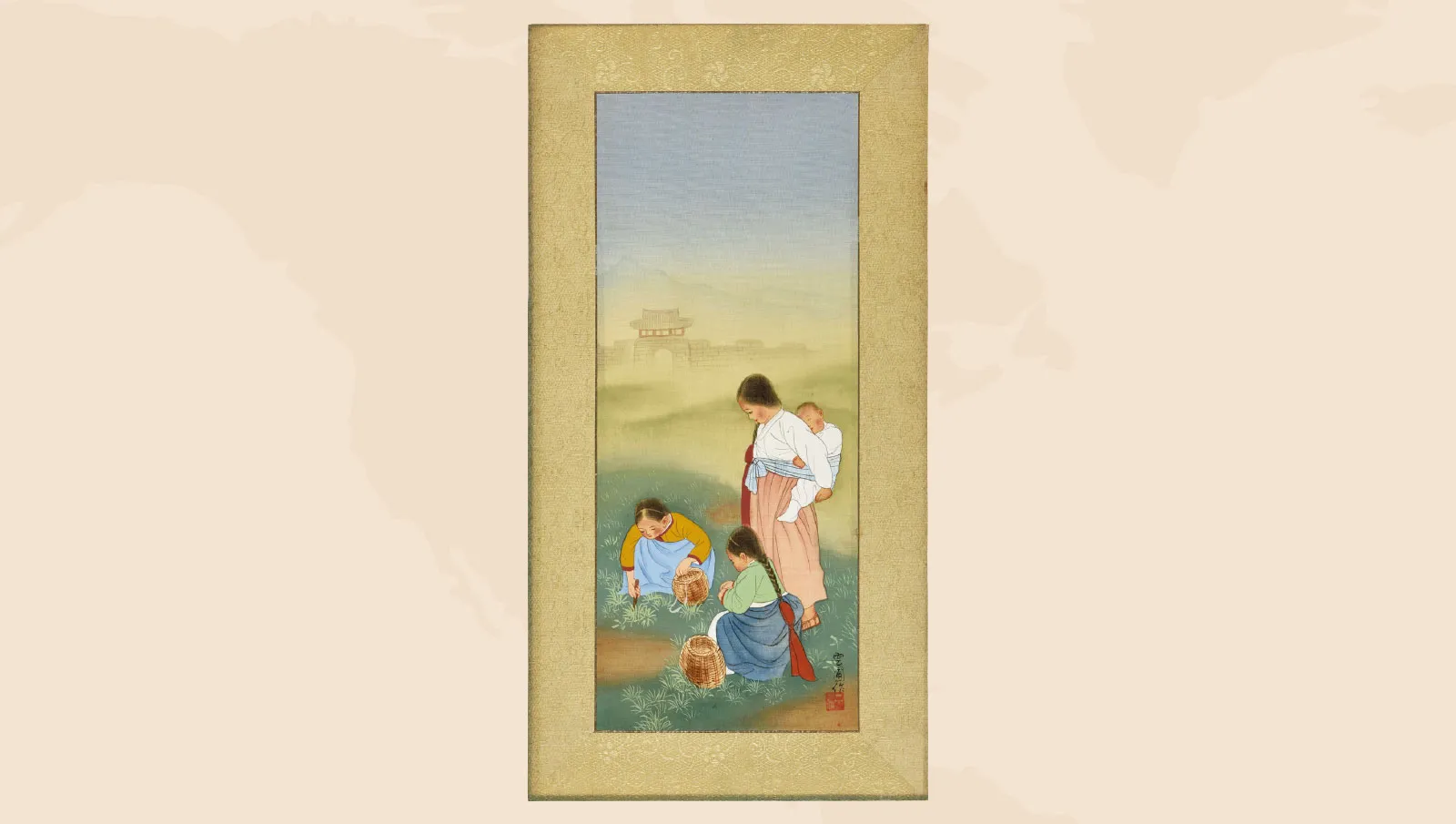

The museum houses not only folk paintings that embody the wishes and aspirations of common people, but also a substantial collection of works that realistically document everyday life of the period. Among the most notable are paintings by the 20th-century artist Kim Ki-chang. Kim worked across a wide range of styles, from traditional East Asian colored figure paintings to abstract works that explored new directions in Eastern painting. He addressed diverse subjects including landscapes, figures, flowers and birds and genre scenes, realistically portraying the daily lives, pastimes and folk customs of ordinary people. Korea’s modest, everyday moments—rendered in simple colors and color planes—unfold scenes from peaceful days hundreds of years ago.

The museum exhibits and preserves Korean paintings depicting various scenes, including “Royal Procession” that capture Joseon Dynasty kings traveling to and from ancestral royal tombs to perform memorial rites. The museum holds within its walls a complete record of Korean life and culture through the ages.

Joseon Memories Captured on

Traditional Paintings

Royal Ontario Museum

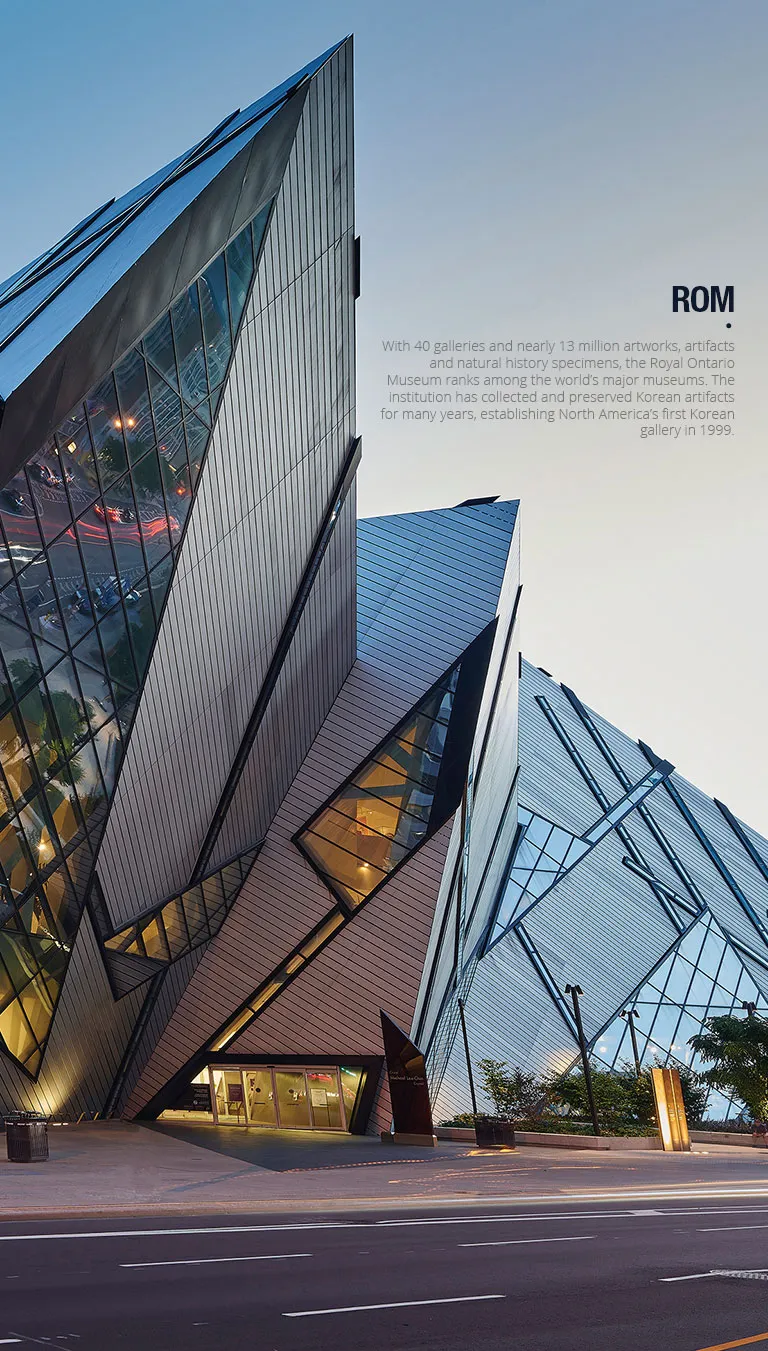

At the Royal Ontario Museum in the heart of downtown Toronto, Canada, Korean history from thousands of years BCE to the modern era has been carefully preserved. Among these treasures, paintings displayed in one gallery still vividly unfold the aspirations and landscapes of Koreans from centuries past.

Recording Life Through Art

How Korea Reached Toronto

The Royal Ontario Museum’s connection with Korea began with James Gale, the first Canadian to visit Korea. As a missionary, he engaged in educational activities in Korea while devoting himself to translation and publishing work. It was during this time that he met the artist Gisan and collected his works along with various Korean art pieces. Later, his son donated this collection to the Royal Ontario Museum, initiating the museum’s first connection with Korea.

Perhaps thanks to this background, the Royal Ontario Museum established North America’s first Korean gallery in 1999 and continues operating North America’s largest permanent Korean exhibition. A Korean curator began working there in 2022, and recently various Korean exhibitions and experiential programs have continued. Approximately 260 Korean cultural heritage items ranging from artifacts circa 8000 BCE to the present day are displayed in diverse forms—ceramics, calligraphy, metalwork, furniture and more.

As interest in Korean culture extends beyond K-pop and K-drama, the Royal Ontario Museum offers a place to explore where it all began. For anyone seeking to understand the roots of contemporary Korean culture, it’s well worth the visit.