One of the most remarkable achievements in Korea’s early space development was the Wooribyeol-3 (KITSAT-3) satellite, developed by the Satellite Technology Research Center of the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST). Launched in May 1999, this 110 kilogram-class satellite carried a multi-channel Earth observation camera with a 13.5-meter resolution—considered high-resolution for its time. This milestone, reached just 10 years after Korea began its space development efforts, built upon the expertise gained from developing KITSAT-1 and KITSAT-2. It was made possible by a forward-looking vision focused on industrial competitiveness—including three-axis attitude control for remote sensing, satellite command and control systems, and high-speed image reception and processing—combined with the dedication of young researchers.

Semiconductor-based high-capacity storage devices are now standard equipment on remote sensing satellites. However, when development began in 1995, integrating this technology into small satellites presented numerous challenges. These ambitious early efforts became a driving force for Korea’s rapid advancement in satellite technology. Success required both the passion of researchers and the strength of Korea’s semiconductor industry. The 10 GB memory module used for image storage notably incorporated Samsung Electronics’ memory chips, showcasing Korea’s semiconductor capabilities.

Lift-Off: Korea’s Aerospace

Industry Takes Flight

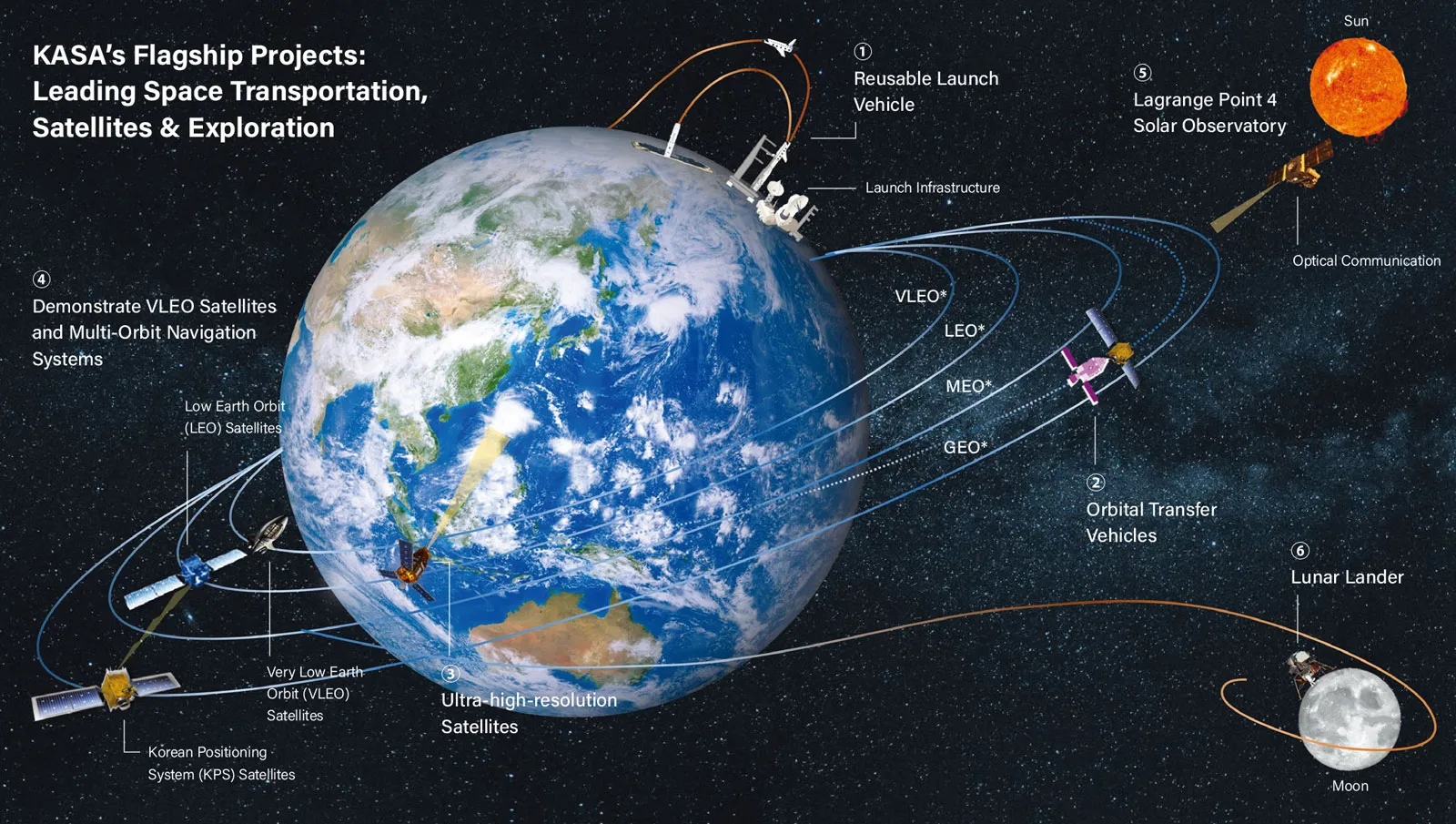

Korea’s space development began with the launch of KITSAT-1 in 1992 and expanded into lunar exploration with the Danuri orbiter in 2022. Space transport capabilities have grown significantly, from the Naro (KSLV-1) rocket’s 100 kilogram payload capacity in 2013 to the Nuri rocket’s 1.5-ton capacity in 2022. The Korea AeroSpace Administration (KASA), established in 2024, is now advancing the development of a lunar lander, next-generation launch vehicles, and a Korean navigation system while fostering a private sector-led space industry.

Meanwhile, Korea’s satellite development capabilities grew dramatically through the Korea Multi-Purpose Satellite (KOMPSAT) program, a comprehensive remote sensing initiative. Camera resolution improved steadily: from 6.6 meters on Arirang 1 (KOMPSAT-1, launched in 1999) to 1 meter on Arirang 2 (KOMPSAT-2), 0.7 meters on Arirang 3 (KOMPSAT-3) and 0.55 meters on Arirang 3A (KOMPSAT-3A), Arirang 7 (KOMPSAT-7), launched in December 2025, achieved ultra-high resolution of 0.3 meters, reaching world-class performance in commercial remote sensing.

Technological development driven by ambitious national goals transformed the Korea Aerospace Research Institute (KARI) into a world-class research organization while catalyzing industry growth. Korean companies’ ability to independently develop remote sensing satellites and distribute imagery stems directly from this government-led satellite development strategy. The government has also promoted industry-led development of geostationary satellites, supporting companies in designing satellite platforms that meet mission requirements. As a result, Korea now operates geostationary meteorological and ocean observation satellites, providing continuous public services around the clock.

While Korea’s satellite program achieved remarkable growth starting in the 1990s despite a later start than other space nations, space transportation lagged behind. Unlike satellite technology, space transportation technology is classified as dual-use (civilian-military), making international cooperation difficult and requiring domestic development of most systems. Beginning with sounding rockets in the 1990s, Korea developed the Naro rocket in partnership with Russia. After two failures, its successful launch in 2013 demonstrated that indigenous launch vehicle development was feasible. The program also advanced industrialization by establishing ground infrastructure—launch pads and tracking systems—in collaboration with domestic companies.

The Nuri rocket, which followed the Naro rocket, is a three-stage vehicle using liquid propellant. After failing to reach orbit on its first attempt in 2021, it demonstrated reliable performance with consecutive successes in 2022 and 2023. The November 2025 fourth launch was particularly significant: it marked the first success after KARI transferred system integration technology to private industry, signaling Nuri’s transition to commercial operations. The fifth launch, scheduled for June 2026, will carry five micro-constellation satellites plus 10 CubeSats developed by universities and companies. The sixth launch in 2027 will deploy 12 domestically-built satellites, including Korea’s first “active debris removal satellite” with space debris removal capabilities for environmental protection demonstrations.

In the early years, the lack of indigenous launch vehicles meant relying on foreign rockets, which severely constrained opportunities to test and commercialize satellite technology. Now, with domestic launch capability, Korean universities and companies have far greater opportunities to validate space-based business models through demonstration missions. The next-generation launch vehicle is being developed to place lunar landers of 1.8 tons or more into lunar orbit by 2032. Importantly, it will be reusable rather than expendable, maximizing cost-effectiveness and operational efficiency.

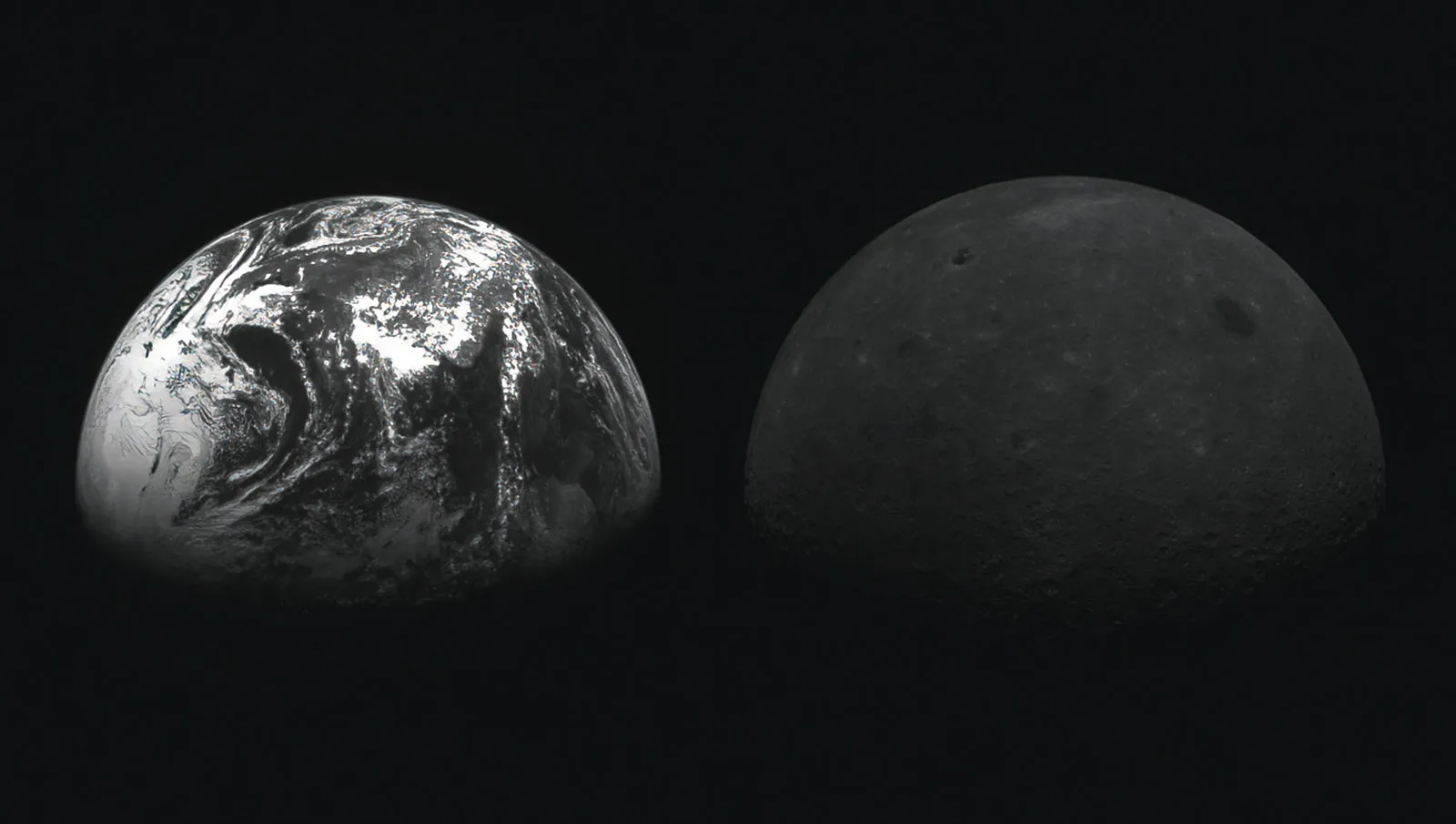

The 2032 lunar lander will carry a rover and instruments to measure the Moon’s environment. Before then, Korea plans to launch a lunar communications relay satellite using the Nuri rocket and an orbital transfer vehicle. Because the Moon is tidally locked to Earth, a communications orbiter is essential for exploring the far side and enabling autonomous rover operations. Such capabilities are increasingly important as international lunar competition intensifies. Looking further ahead, Korea is preparing for Mars exploration through international partnerships, with the goal of developing a Mars lander by 2045. In parallel, the country is pursuing collaborative projects such as solar observation at the L4 Lagrange point—a “parking spot” in space where gravity is perfectly balanced. It is also participating in the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), the world’s largest radio telescope project.

With KASA’s establishment in May 2024, Korea’s space program gained a mission-focused headquarters structure alongside policy divisions inherited from the Ministry of Science and Technology. KASA is formulating space policy across all domains—aviation, space transportation, satellites and space science and exploration—while actively promoting space industry development. The 2026 budget exceeded KRW 1 trillion. To chart a long-term course in space science and exploration, traditionally the domain of spacefaring nations, KASA released a comprehensive roadmap developed with input from academia, research institutions, and industry. Through these efforts, Korea aims to elevate its space capabilities to the next level.