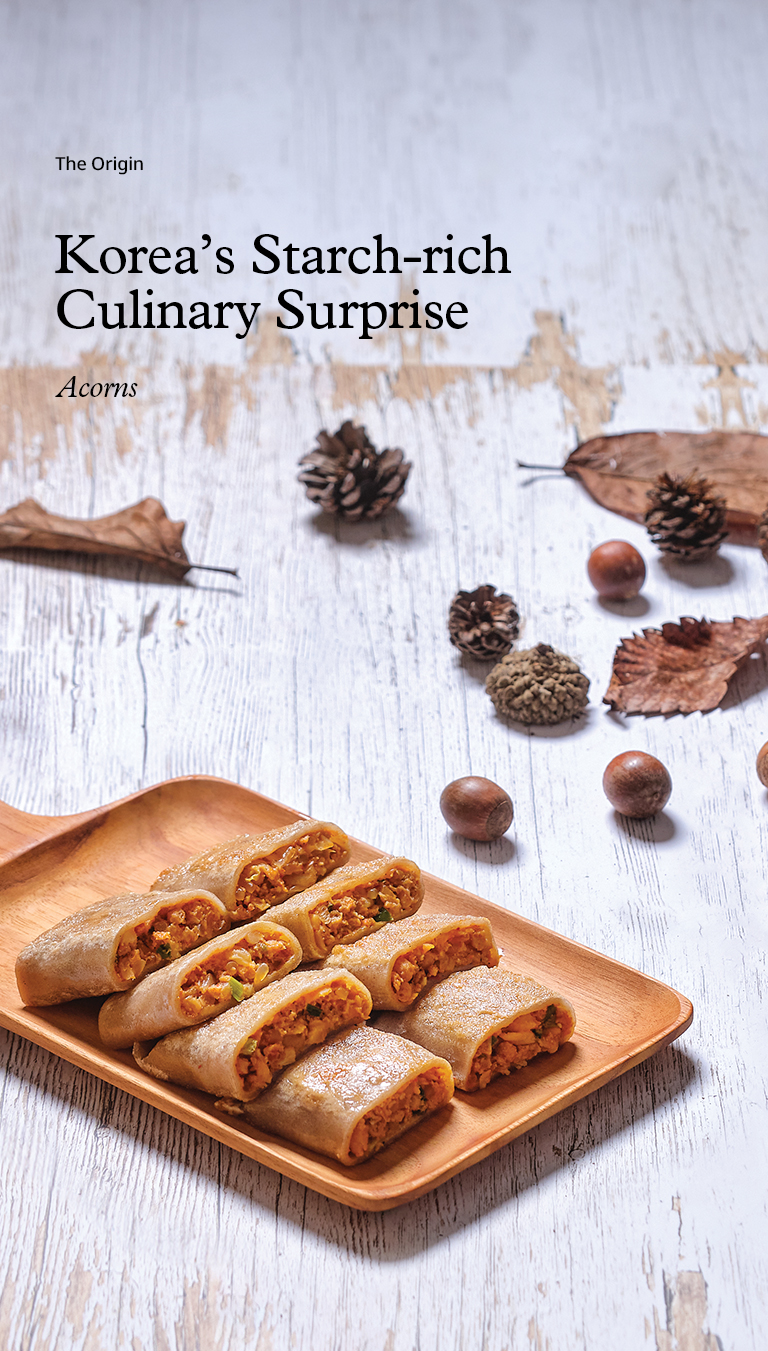

Visiting Korea in the fall months is a must for all nature-lovers. As the trees prepare to shed their leaves, the foliage on the country’s seemingly endless mountains turns from a lush, deep green into a myriad of fiery hues. But underfoot, you will also see acorns—a hidden secret of Korean cuisine.

Writer. Tim Alper

Several species of oak tree are native to Korea, including the eponymous Korean oak (Quercus dentata). To many modern ramblers making their way along mountain paths in the autumnal months, fallen acorns are just part of the scenery. But for Koreans in the past, these little nuts were sometimes the difference between life and death.

In years gone by, Korean farmers spent long hours every day agonizing over meteorological conditions. Would this year’s harvest prove good or bad? And what would they do if the latter proved to be the case? In mountain communities, acorns could sometimes provide the answer.

The old Korean proverb, “Acorns reveal themselves to those who look out at open fields,” still exists today. It reflects the idea that acorns, like crops, were fewer in poor harvest years and more plentiful in good ones. In other words, the number of acorns could serve as a way to anticipate a year of famine or abundance.

Whether this was actually true or not mattered less than the reality farmers faced: if the harvest failed, they would have to forage for acorns to survive, no matter how bitter or scarce they were.

But how did Koreans eat these bitter, unpalatable nuts? As many know, unprocessed acorns are inedible because of one key chemical: tannin. Tannin is extremely bitter—enough to make raw acorns completely unpalatable—and in high quantities, even toxic.

However, Korean communities in mountain areas discovered that removing tannin from acorns is actually a relatively simple process. Their discovery paved the way to unlock a new, low-cost source of nutrition that still enjoys enormous popularity today.

© TongRo Images Inc.

© TongRo Images Inc.

Several Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) documents outline the time-tested methods used to remove toxins from acorns. One of these, found in “Ojuyeonmunjangjeonsango”—a book written during the reign of King Heonjong (r. 1834-1849)—involves crushing whole nuts in a mortar to break them open. After removing their shells, cooks crush the acorns roughly and then repeatedly boil them. Then they soak the nuts in plain water for several days, changing the water periodically. This removes the tannin from the nuts—which are then left to air-dry in the sun for several days. Finally, they are pulverized into a fine powder.

Dotorimuksabal (chilled acorn jelly soup) with long strips of dotorimuk (acorn jelly), kimchi, cucumber and seaweed ⓒ Gettyimages Korea.

Dotorimuksabal (chilled acorn jelly soup) with long strips of dotorimuk (acorn jelly), kimchi, cucumber and seaweed ⓒ Gettyimages Korea.

Another method, from “Yun-ssi Eumsikbeop,” a family cookbook published in 1854, sees cooks peel the acorns before splitting and soaking them. Cooks then blanch the acorns before grinding them and air-drying the resulting paste. The dried paste is then ground and sieved to remove impurities.

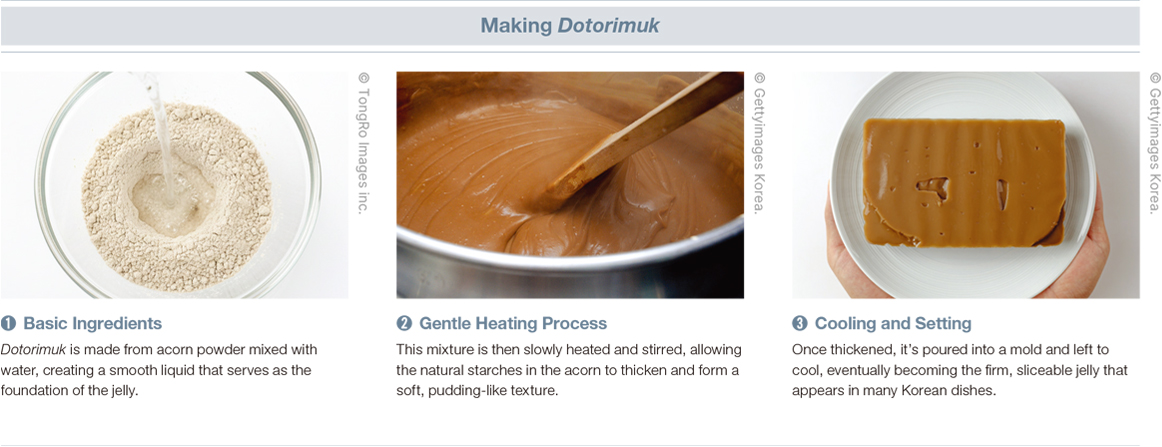

Both of these methods produce a kind of acorn flour, remarkable for its long shelf-life. The diversity of the dishes that inventive cooks can make with this flour is impressive. But this diversity is arguably eclipsed by acorns’ nutritional value.

Due to its high starch content (50-55%), acorn flour can help replace traditional staples in times of famine. Per 100 g, prepared acorns deliver around 387 kcal, along with over 6 g of protein and a generous dose of unsaturated fat. The same portion size of properly prepared acorns also delivers over two-thirds of an adult’s daily required intake of copper, almost 60 % of the manganese you need in a day—in addition to other nutrients like potassium, magnesium, iron and antioxidants.

Koreans consume acorns processed into flour and used in various dishes. © TongRo Images Inc.

Koreans consume acorns processed into flour and used in various dishes. © TongRo Images Inc.

By far and away the most popular Korean dish made using acorn flour is dotorimuk (acorn jelly), a dish so famous it has its own royal origin story. The (possibly apocryphal) story tells of how the King Seonjo (r. 1567-1608) of the Joseon Dynasty fled the royal palaces to escape Japanese invaders.

Seonjo headed to the mountainous north of the country, where he took refuge in a village full of common folk. Unsure what to feed their unexpected guest, and short on food themselves, the village’s cooks hurriedly prepared him a dish of dotorimuk. Tired and hungry from his travels, Seonjo ate this strange preparation—and marvelled at its incredible flavor.

When he returned to the palace, Seonjo insisted that the dish be served to royal diners to help him recall the hardships of the past—and his subjects’ generosity. This event saw the once-humble acorn elevated to the very pinnacle of the Korean food pyramid.

Despite its royal connections, dotorimuk remained an inexpensive and much-loved dish for centuries in Korea. Making it is relatively simple. Cooks mix acorn flour with water, bring the mixture to a boil, and then leave it to cool. This process allows the mixture to set, creating a distinctive brown jelly. Cooks then cut this into uniform strips and season it with ganjang (soy sauce) and other ingredients such as spring onions, sesame oil and garlic.

1. Dotorijeon, thin crepes made by mixing vegetables, water and acorn flour ⓒ Gettyimages Korea.

1. Dotorijeon, thin crepes made by mixing vegetables, water and acorn flour ⓒ Gettyimages Korea.

2. Dotoriguksu, noodles made with acorn flour, boiled in ganjang-based broth ⓒ Gettyimages Korea.

Dotorimuk may be the most popular Korean acorn preparation, but it is certainly not the only one. Some modern cooks like to combine acorn and wheat flours to make acorn pancakes, a slightly firmer pancake—and an ideal foil for vegetable fillings.

The high starch content of acorn flour also makes it ideal for making dishes like noodles, or even as a replacement for rice flour in some Lunar New Year preparations. These include songpyeon, a half moon-shaped rice cake filled with sweet ingredients like red bean paste.

In spite of all this, dotorimuk remains the most ubiquitous of Korean acorn-based dishes—for good reason. While Koreans and visitors alike can often find it a challenge to pick up a piece of dotorimuk with metal chopsticks, they always find that it was worth the effort.

Dotoritteok, rice cake made with acorn flour, red beans and rice flour © National Institute of Crop and Food Science, Agro-Foods Database Platform.

Dotoritteok, rice cake made with acorn flour, red beans and rice flour © National Institute of Crop and Food Science, Agro-Foods Database Platform.

1 dotorimuk, 5 perilla leaves or lettuce leaves, 1/4 onion, 1/4 carrot, 1/4 cucumber, 3 tbsp ganjang, 1 tbsp sugar, 1 tbsp chili pepper powder, 1/2 tbsp corn syrup, 1/2 tbsp minced garlic, 1 tbsp sesame oil, A pinch of sesame seeds